Attila, Leader of the Huns Who Dominated Ancient Europe, Was Korean

The German TV ZDF’s documentary series “Sphinx: Secrets of History,” particularly the episode “Finding the Missing Link,” intensively traced the Huns, the Asian nomadic people who triggered the great migration of Germanic tribes in 375 CE, leading to the fall of the Roman Empire.

This documentary suggested that the origins of the Huns might lie in the easternmost part of Asia - that is, they could be Korean. When comparing relics and remains of the Huns with those of Silla and Gaya people, several commonalities are discovered, including artificial cranial deformation (扁頭, flat heads) and gold crown headdresses.

|

|---|

| Kim Jin-sam’s Portrait of Attila with Oriental Features |

One of the most regrettable aspects of Korean history is that Silla enlisted Tang China’s help to unify the Three Kingdoms. This not only set a bad precedent of involving foreign powers in unification but also resulted in losing all of Goguryeo’s vast territory to Tang China. Therefore, some sarcastically call it unification in name only - “a beautiful but worthless fruit.”

Perhaps because Goguryeo resisted mighty China for hundreds of years while expanding its territory in northeastern Asia, Koreans feel a strong attraction to this fallen great kingdom. Despite unfavorable geographic conditions, Goguryeo once secured the most extensive territory in Korean history. During King Gwanggaeto’s reign (375-413), Goguryeo’s territory extended to the Liao River in the west, Kaiyuan in the north, Okjeo and Ye in the east, and the Han River basin in the south. Historians generally estimate that during the reigns of King Gwanggaeto and King Jangsu (413-491), Goguryeo recovered almost all the territory once held by Gojoseon.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that modern scientific civilization began in Europe. Since around 500 BCE, following Greece, Rome became the political and military “center of the world,” and world history has flowed centered on Europe. During Rome’s domination of Europe, several Asian peoples advanced into Europe, but they failed to completely conquer Rome.

However, the force that destroyed Rome was none other than the Asian people, the Huns. In 375 CE, the Huns, a horse-riding people, crossed the Volga River and attacked the Ostrogoths, a branch of the Germanic tribes, who then attacked the Visigoths. The Visigoths then entered Roman territory and requested protection.

One hundred years after the Germanic tribes began living in Roman territory, in 476, the Western Roman Empire finally fell to Odoacer, a Germanic chieftain. Subsequently, as the Germanic tribes dispersed to various regions including Western Europe and North Africa, new borders were drawn in Europe. Most of these borders established at that time continue to the present day.

The Huns Were a Branch of the Korean People

Recently, evidence from relics and historical records discovered worldwide is revealing that the Huns - who triggered the Germanic migration in Western Europe and pushed the Roman Empire to the brink of destruction - were actually a branch of the Korean ethnic group.

While many people find this remarkable historical claim interesting, quite a few react with “what nonsense is this?” The name “Huns” itself is unfamiliar to us, and they wonder how Korean people living on the Korean Peninsula in the 4th-5th centuries, when transportation wasn’t developed, could have attacked Europe.

However, the historical claim that the Huns were a branch of the Korean people doesn’t necessarily mean that Koreans directly attacked Europe. The Huns were a branch of the Xiongnu (匈奴, a generic term for northern horse-riding peoples), who struggled with China over the Central Plains for about 700 years from the 3rd century BCE to the 4th century CE.

During this process, the Xiongnu experienced constant ups and downs. At this time, some of the Korean ethnic origins included in the Xiongnu advanced westward and grew into the Huns, while another group advanced to the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and became part of the current Korean people.

This claim is based on the following points:

Mongolian spots have been found among Hun descendants living in France and other parts of Western Europe. Mongolian spots are pigmentation changes appearing on the buttocks at the tailbone level and are a physical characteristic that genetically appears in Mongolian-lineage peoples. While Mongolian spots aren’t exclusive to Koreans, the fact that Hun descendants are born with Mongolian spots suggests a kinship connection between Koreans and the Huns.

The Huns used their distinctive Yemaek composite bow (濊貊角弓). The Yemaek composite bow takes 5 years just to make and 10 years to master properly, but it’s known that more than 15 arrows can be shot within one minute. The fact that the Huns used the Yemaek composite bow is evidenced by a fresco in the Cripta Affreschi Church in Aquileia, northern Italy.

|

|---|

| Mounted Warrior Figure Pottery from Silla Period Excavated in Gyeongju, Showing Northern Nomadic Characteristics |

This painting shows Huns on horseback shooting arrows at pursuing Roman cavalry. The scene is identical to Goguryeo warriors on horseback hunting animals with bows in the Muyong Tomb murals. The arrowheads in the tomb murals are axe-blade arrowheads, which rotate as they fly, creating tremendous impact when hitting the target. The Huns also used these axe-blade arrowheads.

Customary commonalities are also being discovered. The Huns’ skulls show artificial cranial deformation (扁頭, flat heads). Scholars analyzed Hun skeletal remains from tombs found along the Huns’ migration route from Mongolia to Thuringia and Odenwald in Germany and Calvados in France, and found that the Huns had unusually flattened temples and foreheads, groove-like wrinkles around the head, and elongated skulls showing cranial deformation. However, flat-head skulls have also been found in Gimhae, Gyeongsangnam-do, where the Gaya Kingdom was founded. Kings of Silla, including King Beopheung, are also said to have had flat heads. Choi Chi-won recorded in the merit monument of Great Master Jijung, a national preceptor of Silla, that King Beopheung had a flat head.

Cranial deformation, known as a custom practiced in ancient India or among nomadic peoples in the northern Caucasus region, has strong connections to the Korean people. The “Weizhi Dongyi Zhuan” (魏志東夷傳) in the “Records of the Three Kingdoms” states that “all people of Jinhan (辰韓) have flat heads.” Also, the custom of creating flat heads existed in Gojoseon from early times. Cranial deformation can be seen as a custom that was very prevalent for a long time among the Dongyi (東夷) peoples, distinct from the Chinese. What’s noteworthy is that while cranial deformation is found among the Huns, it’s not found among the Xiongnu. Therefore, it can be inferred that the Huns who attacked Europe were a special tribe with the flat-head custom and had affinity with the Gaya and Silla regions of southern Korea.

Meanwhile, large and small cauldrons (cup cauldrons) have been found along the Huns’ migration route. These bronze cauldrons, offered to nomadic tribal chiefs and used for offering meat in purification rites, look like large flowerpots. Such cauldrons are also found in the Daeseong-dong and Yangdong-ri sites in Gimhae, Gyeongsangnam-do, Gaya period tombs. Cauldrons have often been cited as evidence that the origins of the Gaya Kingdom and others were northern horse-riding peoples. The Huns carried cauldrons on horseback, and the mounted warrior figure pottery (National Treasure No. 91) excavated from Geumnyeong Tomb in Nodong-dong, Gyeongju, also shows people carrying cauldrons on horseback. Moreover, all the figures in these mounted warrior figures also have flat heads.

Additionally, the patterns found on Hun cauldrons and other items are similar to the headdress styles of Korean gold crowns. Gold crowns excavated in Korea often feature tree shapes (出-shaped decorations) and antler shapes (deer antler decorations). This is also a custom appearing among northern peoples, indicating that northern peoples migrated to and settled on the Korean Peninsula.

Sacrificial burial (殉葬), a typical custom of northern nomadic peoples, is also proven through tombs in the Gaya region. Particularly in Tomb No. 1 of the Daeseong-dong tomb complex, a Geumgwan Gaya site, a wooden coffin was found with the heads of cattle and horses placed on top, which completely matches the animal sacrifice practices of northern nomadic peoples including the Huns.

Records that the Huns hung red cloth on trees to pray that evil spirits wouldn’t approach and that they worshipped bears as peace totems are very similar to how our people erected jangseung (totem poles) or sotdae (bird poles) at village entrances to make wishes and adopted bears as totems. Most nomadic peoples worship animals other than bears. Reindeer and otters, the most common totem objects, are still regarded as objects of worship in the Mongolian region.

Western Huns, Eastern Koreans

Then how did the ancient Korean ethnic origins split into the Huns of the Asian continent and the Gaya and Silla people of southern Korea? This is connected to the rise and fall of the Xiongnu, who began appearing in earnest in Chinese history from the time of Emperor Qin Shi Huang.

The Xiongnu fought long, bloody battles with the Qin Dynasty and the subsequent Han Dynasty over hegemony in the Central Plains. Then in 57 BCE, they split into eastern and western factions and fought each other. When Zhizhi (?支), the shanyu (king of the Xiongnu, meaning “son of heaven”) of the Western Xiongnu, was defeated by Huhanye of the Eastern Xiongnu, he led his clan across the Ural Mountains to the middle reaches of the Syr Darya River. This was the first western migration of the Xiongnu. Zhizhi established a country called “Yating (牙庭)” with Jiankun (between the Chu River and Talas River) as its capital. Western Europe considers this the origin of the Xiongnu Empire’s appearance.

Meanwhile, with the establishment of the Later Han (後漢) in China, the Southern Xiongnu, feeling disadvantaged, led eight groups south of the Gobi Desert in 48 CE and surrendered to Emperor Guangwu (6 BCE-57 CE). Guangwu gave the Southern Xiongnu territory in Inner Mongolia to use them to check the Northern Xiongnu who hadn’t surrendered. Then in 73 CE, the Han Dynasty allied with the Southern Xiongnu to deliver a decisive blow to the Northern Xiongnu. Defeated, the Northern Xiongnu migrated to Mobei (漠北) in northern Asia. This was the second western migration of the Xiongnu. The Northern Xiongnu took control of the Western Regions and gathered their forces to confront the Han Dynasty.

|

|---|

| Daeseong-dong Tombs in Gimhae Where Large Quantities of Representative Geumgwan Gaya Relics Similar to Hun Artifacts Were Excavated |

However, the Han Dynasty again dealt a decisive blow to the Northern Xiongnu in 89 CE, the first year of Emperor He (和帝, 89-105), by rallying the Southern Xiongnu. Mortally wounded and fragmented, most of the Northern Xiongnu became subordinate to the Xianbei (鮮卑), who had separated from the Donghu (東胡). However, some Northern Xiongnu continued westward north of the Tian Shan Mountains, passing through the Fergana Valley to the land of Kangju (康居) between Lake Balkhash and the Aral Sea. This was the third western migration of the Xiongnu.

Another link connecting the Xiongnu and Huns is the Southern Xiongnu who appeared around the collapse of the Han Dynasty. In 304, Liu Yuan (劉淵, ?-310), who was based in Taiyuan, Shanxi, was enfeoffed as king of the Southern Xiongnu by Emperor Hui of Jin (晉). However, Liu Yuan claimed to be a descendant of the Han Dynasty based on having a Han princess among his ancestors and proclaimed himself emperor. He established Northern Han (北漢, i.e., Former Zhao) in Taiyuan in 308. In 318, Shi Le (石勒, 274-333) abolished the Former Zhao and established a new Xiongnu state known as Later Zhao (後趙), and in 349, Shi Min (石閔) seized power in the Later Zhao. Shi Min incited the Han people (漢人), who harbored deep resentment against the Xiongnu, to launch a massive Xiongnu subjugation campaign, then stood by as more than 200,000 Xiongnu were killed.

For the Xiongnu, this was a decisive defeat. When the Xiongnu assimilated into China and those maintaining nomadic life were defeated despite their alliance, the surviving Xiongnu fled westward seeking new territory. This was the fourth western migration of the Xiongnu, and they joined (or pressured) the Xiongnu who had already migrated west in the first through third migrations. To make matters worse, when severe cold waves struck from around 370, the Xiongnu migrated further west, attacking Western Europe in 375.

Meanwhile, the regions on the Korean Peninsula where affinity with the Huns is most prominent are Gaya and Silla, and it’s very likely that some of the Hun ruling groups migrated east (東遷) and settled on the Korean Peninsula during wars with China. Here, the ruling groups of the Huns refer to tribes to which the nomadic chiefs belonged.

Scholars note that the rise and fall of northern horse-riding peoples such as the Xiongnu, Donghu, Xianbei, and Wuhuan coincide with the founding period of the Gaya Kingdom. According to the “Weizhi Dongyi Zhuan” in the “Records of the Three Kingdoms,” Mahan, Jinhan, and Byeonhan (the Three Han) existed in the south-central part of the Korean Peninsula until at least the 1st-3rd centuries. After the mid-3rd century, Mahan was integrated into Baekje and Jinhan into Silla, and Byeonhan came to be called Gaya after the 3rd century. This not only means that Byeonhan transformed into Gaya society in the late 3rd to early 4th century but also shows that unlike Silla or Baekje, Gaya encompassed various different states internally. Depending on the scholar, the founding period of Gaya shows as much as 5 centuries of difference, from the 2nd century BCE to the mid-3rd century CE, causing much controversy.

Scholars argue that the very discovery of typical northern horse-riding people’s relics in Gaya tombs in Gyeongsang Province is evidence that northern horse-riding peoples settled on the Korean Peninsula. There’s even a theory that the Xiongnu directly entered the Korean Peninsula and founded Geumgwan Gaya. Considering these points, the claim that a branch of the Korean people included in the Xiongnu migrated west and grew into the Huns, while another branch migrated east and grew into Gaya and others, gains persuasiveness.

Demanding Half of Rome as a Marriage Condition

If we were to name historical figures who built the largest great kingdoms, we would include Genghis Khan, Alexander the Great, and Attila (395-453). Attila, who built one of the world’s three great empires, was born as the second son of King Mundzuk in 395, 20 years after King Gwanggaeto of Goguryeo and 20 years after the Huns invaded Western Europe. Attila’s life is relatively well known through the Roman historians Priscus and Jordanes.

Rome gave tribute to the Huns to maintain peace while being wary of the Germanic tribes. Accordingly, following diplomatic customs of the time, Attila grew up in the court of Ravenna, the capital established by Western Roman Emperor Honorius, from around 410.

When his uncle Ruga, who was the successor to the throne, died in 434, Attila ascended to the throne together with his brother Bleda, following Hun tradition. As new kings seeking opportunities to demonstrate their power externally, when the Eastern Roman Empire repeatedly failed to pay tribute on time to the Huns, they advanced on Eastern Rome in 435. In response, Eastern Rome agreed to double the tribute and signed a peace treaty with Attila. Subsequently, Attila received police authority over the Visigoths from Western Rome. Thus, the Huns effectively became the hegemon of Europe, surpassing the Roman Empire.

When Bleda died in 443, Attila became the sole leader of the Huns. Attila’s Hun Empire’s dominion extended from the Balkan Peninsula in the south to the Baltic coast in the north, the Ural Mountains in the east, and present-day France in the west - truly vast territory. The number of tribes under his rule reached 45.

At this time, a woman appeared who drew Attila into international warfare. That woman was Honoria, the sister of Western Roman Emperor Valentinian III. In 450, Honoria was discovered and exiled to a monastery in Eastern Rome for plotting to overthrow her brother from the imperial throne. Honoria then sent her gold ring to Attila, whom she had known well since childhood, requesting rescue. At that time, sending a ring meant a marriage proposal. Attila demanded half of the Roman Empire as a dowry from Valentinian III. However, Valentinian III rejected Attila’s request and married Honoria to another man.

Feeling betrayed by Western Rome, Attila attacked the Gallic region in 451, which now includes Belgium and the French cities of Metz, Reims, and Orléans. Attila’s army advanced with overwhelming force to the heart of Western Rome. In response, Western Rome appointed Aetius, Attila’s friend known as “the last of the Romans,” as commander-in-chief and rallied Germanic tribes hostile to the Huns to oppose Attila.

On June 20, 451, one of the world’s 15 major battles, the “Battle of the Catalaunian Plains,” took place near the city of Troyes, France. It was a large-scale battle with about 200,000 troops on each side, resulting in 150,000 casualties. However, there was no victor.

After the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains, Attila withdrew to Pannonia (present-day Hungary) and invaded Western Rome again the following year, 452. This time, the Italian Peninsula was the target. Starting with the capture of Aquileia, Attila swept through all of northern Italy including Padua, Verona, and Pavia. It’s said that the name Venice derives from Romans fleeing to coastal areas to avoid the Huns’ attack, crying “Veni etiam (I too came here).”

Futile Demise, Europe’s Hatred

However, Attila and the Huns’ end was too futile. In 453, Attila married a Germanic chieftain’s daughter called Ildico (or Hildico), and was found dead as a cold corpse the morning after the wedding. The famous Germanic epic “Song of the Nibelungs” depicts Ildico, called Kriemhild, harboring resentment for her family being killed by the Huns and murdering the sleeping Attila. However, scholars estimate that Attila either suffocated from excessive drinking on the wedding night or was killed in a power struggle over succession.

When the powerful leader Attila died, his son Dengizich became the leader of the Huns. However, the Hun Empire, composed of various tribes, began to fragment, and after suffering a humiliating defeat to Eastern Rome in 469, it disappeared from history.

Most of the Huns defeated by Eastern Rome returned to the region north of the Caspian Sea. However, some gave up nomadic life and settled in southern Russia and the Crimean region. Some tribes also settled in France and Switzerland. At this time, some Huns are estimated to have remained in Pannonia and later combined with the Magyars to form the Hungarian people. Even now, the Szekely people of Transylvania (present-day Romania) believe they are descendants of Attila the Hun. In Romania, where the legend of Count Dracula has been passed down, Attila is regarded as the prototype of Count Dracula with powerful strength.

Attila was one of the few rulers in world history with tremendous charisma. Children are attracted to the strength, passion, and enormous power associated with his name. The fact that Attila didn’t just engage in destruction and plunder adds to the mystique. Attila also demonstrated diplomatic skills in obtaining much information from opponents through clever negotiations. He asserted his claims while seated on his saddle when dealing with Rome, the world’s most civilized nation at the time, and showed the audacity to demand half of Western Rome as a marriage dowry for Honoria.

However, Attila is simultaneously one of the figures receiving harsh criticism from Europeans. He frequently appears as a cruel tyrant in European novels, plays, and operas. In Canto XII of the Inferno in Dante’s “Divine Comedy,” Attila is depicted suffering in hell.

On January 23, 1968, when the American vessel USS Pueblo was captured in the waters off Wonsan, Attila was once again on people’s lips. Lloyd Bucher, captain of the Pueblo captured by North Korea, apologized to the North Korean side, saying it was “the most unwise action since Attila.” The reason Attila is the target of such harsh criticism from Westerners is that he, an Asian, ravaged the heart of Europe including Germany, France, and Italy, trampling their pride.

However, until now, the Huns and Koreans have been regarded as having no connection to each other. This is because even if the origins of the Huns were the Xiongnu (Mongolian-Turkic), the ruling group of the Huns was assumed to be Western Turkic peoples.

However, historians estimate that while the Xiongnu were a mixture of Mongols, Tungus, and other northern peoples, their political ruling group was of Turkic lineage based on studying the linguistic characteristics of the Xiongnu. Scholars including Shiratori Kurakichi claim that the Xiongnu were not Turkic but Mongolian lineage, yet agree that the Xiongnu had Turkic characteristics.

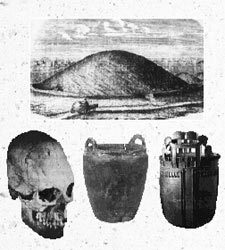

|

|---|

| From top clockwise: Northern peoples’ kurgan similar to Gaya and Silla tombs, Hun cauldron, cauldron excavated from Daeseong-dong in Gimhae, Hun cranial deformation |

The Turks are written as Tujue (突厥) in Chinese characters and belong to the Western Rong (西戎). After breaking free from Mongolian nomadic influence in the mid-6th century, the Turks destroyed the Byzantine Empire in Constantinople in 1493 and formed the great Ottoman Turkish Empire (present-day Turkey).

The Greek historian Zosimus described the Huns as having “shapeless lump-like faces,” with “dark skin, two dark holes instead of eyes, flat noses, and scarred cheeks.” Here, “two dark holes instead of eyes (meaning small eyes) and flat noses” is undoubtedly describing Asian faces.

Sidonius Apollinaris, Bishop of Clermont, also showed strong aversion to the Huns, writing: “Physically and mentally they inspire disgust. Their noses are shapeless and flat, and their cheekbones protrude. Their two eyes have eyelids that open so small that light can barely enter, yet these penetrating eyes can see much farther.” This description is also of Asian, not Western, faces.

The most noteworthy material is the Greek Priscus’s description of Attila’s appearance. Priscus stayed at Attila’s court as a member of the Eastern Roman delegation in 449 and met him several times. In Book 7 of his “History of Byzantium,” of which only parts remain, Priscus described Attila as having a typical Hun appearance. He explained that Attila was “short in stature with a broad chest and large head,” and “had narrow, slit eyes, a flat nose, protruding cheekbones, and a sparse beard.”

Sima Qian also described the Xiongnu as having typical Asian features:

“Their bodies are small but sturdy, their heads very large and round, their faces broad with protruding cheekbones. All their hair is cut off, leaving only the crown. Their eyebrows are thick, their pupils burn intensely, and their eyes are slit-shaped.”

Meanwhile, an anecdote about Sun Zhen (孫珍), crown prince of the Later Yue (後越), descendants of the Xiongnu, asking Cui Yue (崔約), a Han chamberlain, about treatment for eye disease shows that the appearance of Mongols and Chinese were distinguishable.

When Sun Zhen asked “How can eyes be submerged in water?” Cui Yue answered, “Your eyes are sunken so they can be directly submerged in water.” Angered by this remark, Sun Zhen killed Cui Yue and his son. According to this anecdote, the Xiongnu Sun Zhen, unlike the Han people, had sunken eyes and a high nose.

Thus, while Sima Qian described the Xiongnu as Asian and Cui Yue as Western, it’s not strange that the Xiongnu, who had vast territories with many tribes, were composed of people with different appearances.

Present-day Turks, descendants of the Ottoman Turkish Empire built by Turkic peoples, are clearly distinguishable in appearance from Koreans. The physique of Turks is by no means small compared to Europeans, especially ancient Romans. Their noses are also as high as Europeans’. However, because Eastern Roman emperors called Hun leaders “Turk princes” in Altaic, meaning “strong person,” it was assumed that Huns were Turkic peoples. Moreover, historically, the period when Turkic peoples emerged as a united ethnic group was 200-300 years later than when the Huns advanced into Europe, from the 6th century onward.

The Western Roman Empire, which had a standing army of 600,000, fell to the barbaric Germanic tribes in 476. However, what wounds European pride is that the force that drove out the Germanic tribes was the Huns, even more barbaric than the Germans.

However, because the fact that European history was rewritten by the Huns cannot be denied, European historians show a somewhat ambiguous attitude. They console themselves that although the Huns invaded Europe and established an empire, Hun rule over Europe lasted only about 100 years (375-469).

Our Ancestors Who Dominated East and West

When connecting archaeological relics and historical records found along the Huns’ migration route with those of Koreans, there are sufficient grounds to view the ruling group of the Huns as Korean. This has very important meaning for Koreans.

Generally, Koreans have a “small complex” that the Korean people contributed almost nothing to world civilization and only received benefits from China and others. Deeper research into the Huns and Attila will help resolve this complex.

Let’s go back to the 4th-5th centuries. In the West, the Huns ravaged the Roman Empire, and in the East, Goguryeo dominated a vast area of northeastern Asia. Of course, the Huns are estimated to be more closely related to Gaya (Byeonhan) and Silla (Jinhan) than to Goguryeo, but they are all Korean people. When we regard Attila as an ancestor of the Korean people, we gain two proud ancestors who each reigned as hegemons in the West and East during the 4th-5th centuries: Attila and King Gwanggaeto.

1. ZDF Sphinx Series Episode on the Huns

Title: “Todesreiter aus der Steppe - Die Hunnen stürmen Europa” (Death Riders from the Steppe - The Huns Storm Europe)

Broadcast: January 22, 1995, ZDF

Production Team:

2. Content Overview (Atlantis-Film Production Company Information):

3. Korean Connection Theory - “Hun And Forgotten Korea” (2018)

Author Jhongkyu Leeh (Dr. Lee Jong-kyu, PhD from University of Exeter) explicitly states in the book:

“Taking the form of answering questions raised by German ZDF public broadcasting and Discovery Channel in the United States at the end of the 20th Century”

Cultural evidence that the Kim clan of Silla Dynasty were Huns (Xiongnu):